I’ve always loved Renoir. When I was given a pack of pastels at age nine, my first act was to recreate Two Young Girls at the Piano. This knockoff—stylistically crude but visually inoffensive—hung above the piano for most of my young life. When I finally made it to the Musée d’Orsay, just this past year, I shared a photo of the real thing with my brother. He cheekily replied, “Yours was better.”

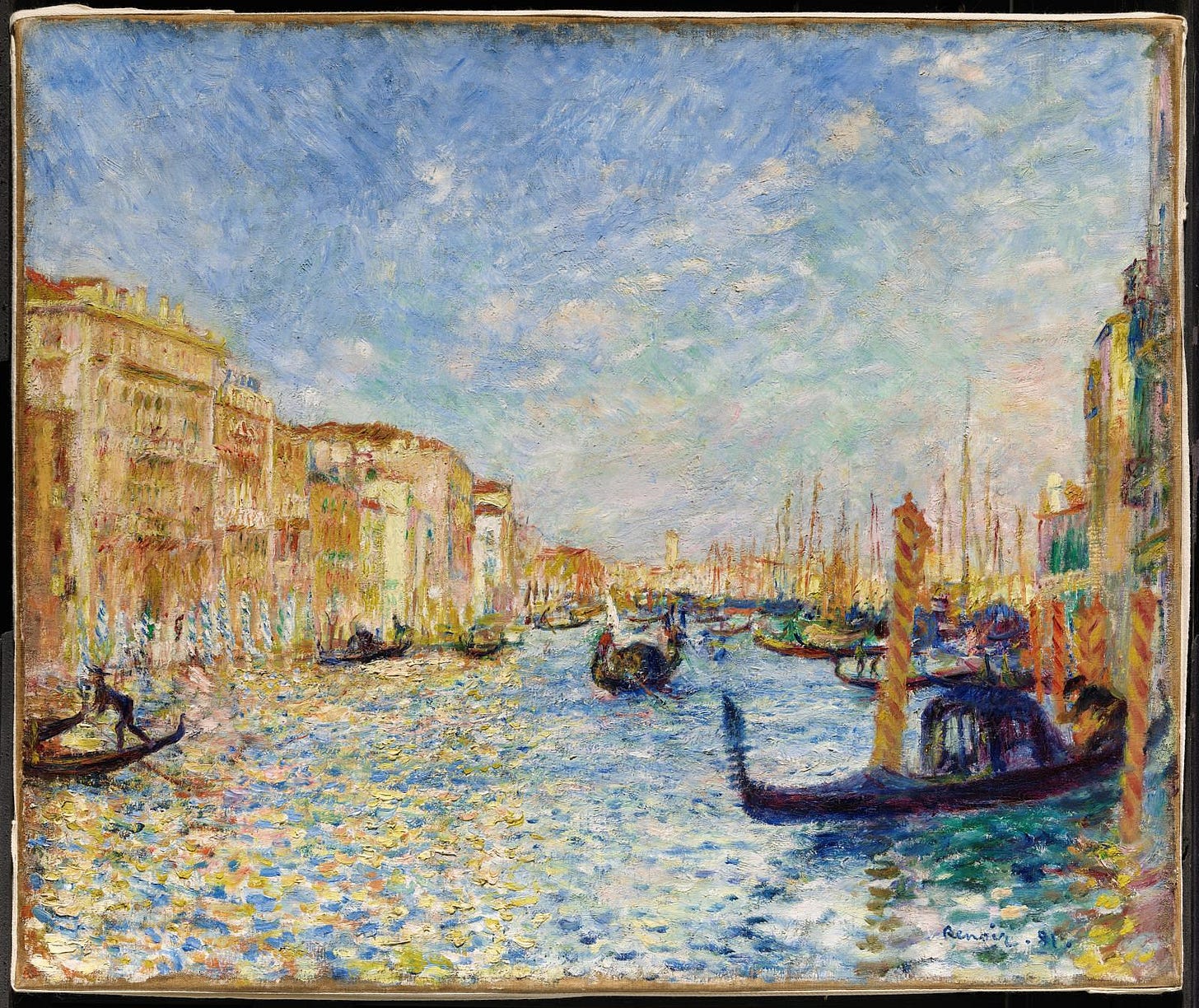

The first thing I do in any museum is seek out the Renoirs. Thanks to his prolificacy, I am nearly always in luck. These artworks tend to be objectively remarkable, of course, but there is also a sting of nostalgia, of childhood, of love for something because it is beautiful and well made. Renoir’s painting of the Grand Canal is a compelling, evocative work, aligned with the artist’s usual palette, yet distinctly Venetian. It is also a painting of a place that is disappearing. Depending on the acqua alta, Renoir painted perhaps 30 centimeters of the buildings along the canal that will never be seen again.

Art offers an occasion to see the world through another’s eyes, and I am often pleased to see the world through Renoir’s. I laughed upon learning how differently Italy’s élite first received his vision—one critic called it “the most outrageous series of ferocious daubs that any slanderer of Venice could possibly imagine.” Such stories are common in art history. Artistic invention is, at the outset, often branded as heresy. But if we are fortunate, time passes, and what we once renounced hangs on the walls.

Acqua alta, or “high water,” refers to the periodic flooding of the Adriatic Sea. The floodwater can temporarily flood Venice.

A. J. Bermudez is the author of STORIES NO ONE HOPES ARE ABOUT THEM (University of Iowa Press, 2022), and is winner of the Iowa Short Fiction Award, the PAGE Award, the Diverse Voices Award, and the Alpine Fellowship Writing Prize.