Again. History drew a circle in the dirt before the wheel was ever invented.

My dark-skinned son describes a circle. “Look, I’ve been pulled over by the police four times in the last year.” It keeps happening. This time the officer says, “Just checking that your headlights are on.” How can this man not see the light?

George Floyd is killed, and a strange thing happens with some well-meaning white people. They start passing their guilt around in a circle. They hope their Black friends will take it from them, absolve them. They send even minor acquaintances text messages, which baffle them.

A Black man is shot in the back by a white police officer.

A Black man is shot in the back by a white police officer.

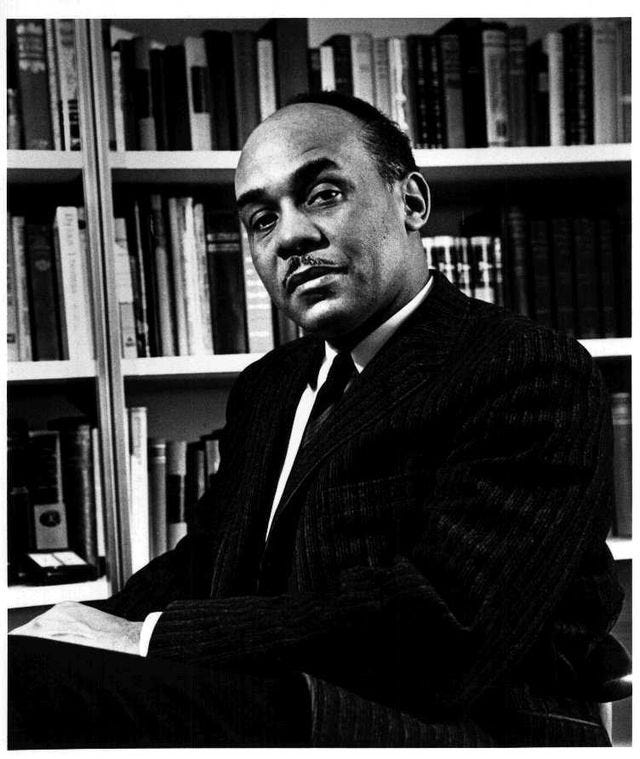

It keeps happening. Not in 2020, but in post-war Harlem in Ralph Ellison’s 1952 award-winning novel Invisible Man. The narrator, an unnamed, young Black man from the South, watches the funeral procession, which resembles a circle that might link up with a procession anywhere – in Minneapolis, in Houston. He scans the crowd. “Why were they here? … Because they knew Clifton? Or for the occasion his death gave them to express their protestation? … Was either explanation adequate in itself? Did it signify love or politicalized hate and could politics ever be an expression of love?”

The questions flow raw and honest. Ellison ends them with a word I circle and circle again.

Before the pandemic, Laura English taught Creative Nonfiction face-to-face to promote the art of truth.

Ralph Waldo Ellison (1913-1994) was an American novelist and scholar best known for his novel Invisible Man. The book explored the social and political issues targeting African Americans in the 20th century.