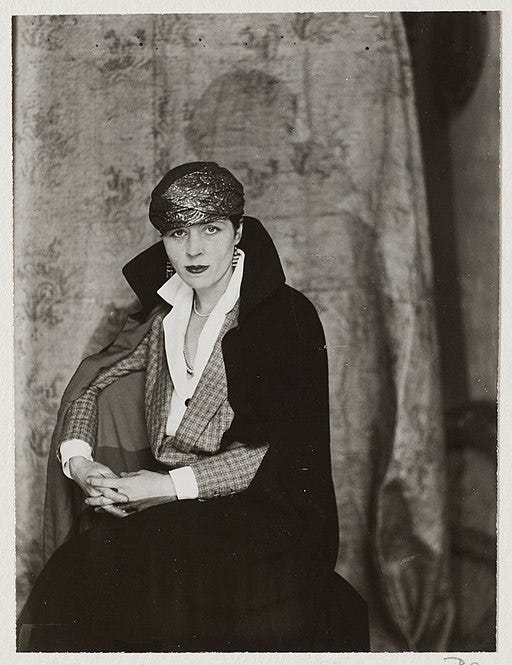

Open Canon: Djuna Barnes

by E.R. Zarevich. Best known for her novel 'Nightwood,' Djuna Barnes is regarded by the LGBTQ community as a writer who dared.

When the 1936 novel Nightwood was published, its readers—and especially its reviewers—didn’t quite know what to make of it. The book already evoked controversy just by existing; lesbianism wasn’t a commonplace topic in American literature at the time, and Radclyffe Hall’s 1928 output The Well of Loneliness, the more prominent lesbian-themed work of fiction at the time, wasn’t exactly winning over fans among the conservative English either. But what constitutes Nightwood’s reputation as being such a bafflingly bizarre novel is its style as much as its content. A blend of traditional Gothic and metafictional modernism, the book was described by one amazed reviewer as “The Twilight of the Abnormal.” The active and unrestrained mind behind this avant-garde masterwork was Djuna Barnes (1892-1982), whose other claims to fame include The Book of Repulsive Women (1915), Ryder (1928), The Ladies Almanack (1928), and an exclusive interview with James Joyce for Vanity Fair in 1922 (an impressive achievement in professionalism, as she was reputedly very jealous of the success of his magnum opus Ulysses). But she is best known for Nightwood and is remembered fondly in the LGBTQ community for being a writer who dared.

Barnes was born in 1892 on Storm King Mountain, a fitting name for a birthplace of such a literary giant. Her family was intellectually accomplished, but financially unstable and abusive, and Barnes would portray these experiences in her works with such disturbing accuracy that it would put her at odds with her family later in life. But nothing, not even family feelings, and especially not societal expectations for women, would stop her from working and creating on her own terms. In 1913, after moving to New York City with her mother and siblings, Barnes marched into the office of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and announced, with outstanding confidence and conviction: "I can draw and write, and you'd be a fool not to hire me.” She must have made an impression on the editor-in-chief. Before long she was the newspaper’s top reporter, and she was doing freelance work for other publications as well, hustling to pay the bills as her family’s main breadwinner. Her most notorious exploits for good stories include crawling into a gorilla’s cage, staging a mock rescue with local firefighters, being subjected to force-feeding (for an insider feature on the Suffragists), and listening to James Joyce prattle on about Ireland. She was also involved with the theater scene and performed and partied with the Provincetown Players in Greenwich Village, where a handful of her one-act plays made their debut. Though her professional life thrived, her love life was messy. Barnes was bisexual and seemed drawn to lovers as troubled as she. A female lover of hers died of tuberculosis, while a male one, a future Nazi, dumped her for not being German and went on to become a close associate of Adolf Hitler. The great tragedy here is that neither of these would turn out to be her worst romantic experience.

The inspiration behind Nightwood’s plot came from what was probably the most toxic bohemian relationship in Paris in the wild 1920s (an incredible feat in its own right). Barnes’s partner during her years in Paris as a foreign correspondent for McCall’s was Thelma Wood, a sculptor and silverpoint artist who was more interested in love affairs than in producing any everlasting masterpieces. A harrowed Djuna Barnes lost her own valuable work time stalking her unfaithful lover around the cafés and nightclubs of Paris. This cat-and-mouse chase and its subsequent heartbreak traumatized Barnes, but it made good book material. Barnes, in Nightwood, represents herself as Nora Blood. Nora’s inconstant lover, Robin Vote, is Wood. And Wood’s other lover, Henrietta Alice McCrea-Metcalf, appears as Jenny Petherbridge. T.S. Eliot, the first publisher of the book—he was an editor at Faber & Faber—made some heavy edits to the manuscript and released it to the unsuspecting public in 1936. It cemented Barnes’s prestige as a cutting-edge, modern novelist, but fame wasn’t enough to rescue her from falling into an irreversible state of alcoholism and drug addiction.

Djuna Barnes lived out the last 43 years of her life in New York City. Though she became a recluse, and wanted to immerse herself in privacy and obscurity, her admirers had other ideas. The diarist Anaïs Nin wanted Barnes to collaborate with her on a magazine (Barnes said no). The Southern Gothic writer Carson McCullers stalked Barnes’s apartment building, hoping to meet her and befriend her (Barnes yelled at her to go away). The poet E.E. Cummings lived nearby and, in a neighborly fashion, regularly checked in on her, and tried to play nice, but Barnes was done with artistic friendships. However, history is not done with Djuna Barnes, and her legacy remains that of an experimental writer who never shied away from her queerness, nor did she allow popular opinion to dictate her creativity when it came to her fiction, plays, poetry, and journalism. Nightwood stands as her masterpiece, a testament to what a prolific mind is capable of without prejudice or constraint.

E.R. Zarevich is an English teacher and writer from Burlington, Ontario, Canada. Fascinated by women's literary history, her biographical articles on female writers have been published by Jstor Daily, The Archive, Early Bird Books, and The Calvert Journal. She is also a writer of fiction and poetry.