Open Canon: Albert Pinkham Ryder

by John McMahon. The painter, a master of building texture to create a unique sense of light, stopped painting after completing one of his most unusual works.

As a young man, I knew exactly where all three of A. P. Ryder's paintings hung in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. These pieces, diminutive even for easel paintings, were like three odd jewels almost hidden in a corner of the American wing. I would go there to study these tortured-looking paintings. They were like nothing else in the museum, their skins cracked and oozing oil from thick brushstrokes, with paint globs in some parts and scraped down to the gesso in others. I didn’t know much about technique at the time, and these were the only Ryders I had ever seen, I don’t know that I understood then the effect of light he was trying to capture, but the paintings had done their job and grabbed my attention.

Ryder’s The Race Track (Death on a Pale Horse) is possibly the most notorious painting in a body of work known for being odd by a painter whose career and life remain somewhat of a mystery. He was active for about 30 years and yet generated fewer than 200 paintings. Regardless, he gained both commercial and critical success and was sought out long after he retreated into a self-imposed hermitage in his New York apartment. Death on a Pale Horse was the last major work he painted and perhaps the reason he stopped painting all together.

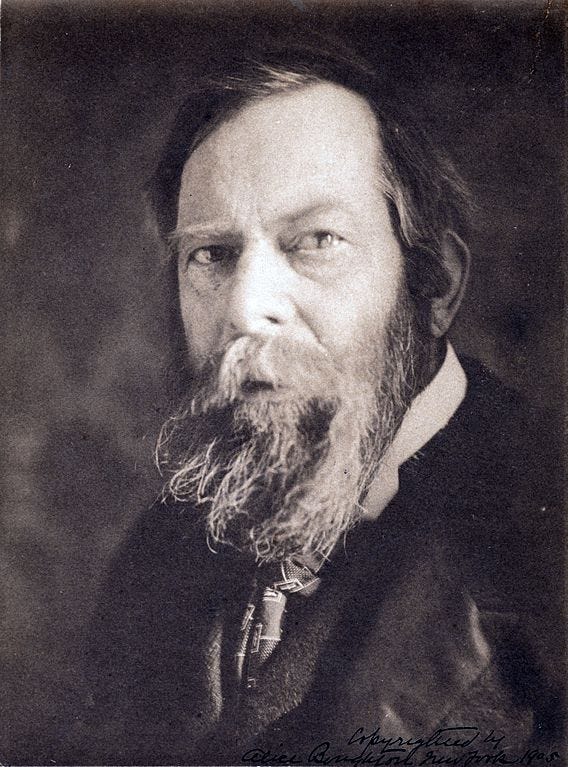

Alpert Pinkham Ryder was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1847, just about the time Herman Melville was making the town infamous by writing it into his forthcoming masterpiece Moby-Dick. Little is known about Ryder’s childhood or early life until his family uprooted and moved to New York City in 1867 to join his brother who was having great success there as a restaurateur.

He was apprenticed to portraitist and miniature painter William Edgar Marshall from 1870-73, 1874-75. At the same time, he studied at the National Academy of Design where he exhibited his first work in 1873. Ryder's first known works were much like those of his contemporaries: open-air landscapes where men worked with their animals, appearing minuscule against the immensity of wild nature all about them.

In 1877 Ryder traveled to Europe for the first time. When he returned, the influence of contemporary symbolism he saw in France became evident in his work, which also had become less vibrant in color but more nuanced in tone. Some of his pieces from this period are almost monochrome. Back in New York, he helped found the Society of American Artists with whom he showed his work from 1878 - 1887.

By the mid-1880s his paintings began to focus on scenes from literature, operas, and Bible verses. These dramatic pieces used elements from the Barbizon School that was popular in France at the time and the Dutch tonalists, but his style was becoming ever more unique. He experimented with layering heavy paint over still-wet coats of paint beneath. He scraped and layered his paintings, searching for a way to create a luminosity that emanates from within the painting. This technique was perhaps most effective in the nocturnal seascapes under the moonlight for which he is probably best known.

In 1895 Ryder painted The Race Track ( Death on a Pale Horse), which would have marked a new period for him if it hadn’t been his last major work. The canvas size is larger by half than his usual work. The paint body was slightly thinner, but he was still employing the techniques he had worked and reworked to create the haunting light of the piece.

He painted the work in effigy of a friend, a waiter who served in his brother’s restaurant, who committed suicide after losing his life savings at a horse race, a sure thing, that like most sure things, wasn't.

“…[the waiter] told me that he had saved up $500 and that he had placed every penny of it on Hanover winning this race. The next day the race was run, and, as racegoers will probably remember, Hanover came in third. I was immediately reminded that my friend the waiter had lost all his money. That dwelt in my mind, as for some reason it impressed me very much, so much so that I went around to my brother’s hotel for breakfast the next morning and was shocked to find my waiter friend had shot himself the evening before. This fact formed a cloud over my mind that I could not throw off, and 'The Race Track' is the result.” In the artist’s own words as reprinted in McBride, “News and Comment,” quoted in Broun, Albert Pinkham Ryder, 1989.

The racetrack centered in the painting's almost otherwise barren landscape disappears over the horizon in an infinite loop. The course is surrounded by a shabby fence that is already broken open just at the viewer's eye level where a fat serpent hovers, flicking its tongue towards the almost skeletal rider on its pale horse. The painting is rich with symbolism. Death rides the pale horse forever, always just on the other side of a fragile border which is broken open by the serpent of temptation who guides the viewer towards the track and into the reach of Death's great sweeping scythe. The only tree that stands is dead, perhaps a farm long abandoned fuses with the forest in the background under what seems an indifferent sun that casts a cold light.

The death of his friend must have affected him deeply for this to be his last major painting, one that he worked on for as many as fifteen years. Building it up, scraping it down, submerging it in tin-lined drawers full of oils as he did with so many of his pieces. From 1900 on he did little more than rework old pieces as he slipped into a kind of self-imposed exile among his rooms.

Still, his paintings remained popular and he was a venerated personality in the art world. Younger painters and artworld hangers-on sought him out and he welcomed them into his home, cluttered and filthy as it was reported to be.

In 1913 he was honored by his peers to hang ten pieces at the now-famous 1913 New York Armory show, a show that established New York’s place among the cities of Europe where great art was being made and could be viewed. It was the first major show of modern art in the United States and resulted in a lawsuit that defined modern art in terms of tax duty compared to appliances, a judgment which import-exporters still go by.

By 1915 Ryder's health was failing and he ceased working altogether. In 1917 he died among friends who took care of him at the end of his life. Ryder’s popularity waned in general postwar, as American art took on a grander scale, even though many of those artists were inspired by his work. For painters, though he has always been there to study. Like some sort of alchemist, he transformed his works into living things with sagging skins that cracked, bunched, and split, releasing trickles of amber from their wounds. There’s no doubt that his paintings look different today from when he painted them because of their never-drying properties, but they still retain the ethereal light he sought with his technique.

John McMahon is a freelance writer/former art world schmuck who now lives on a beach in Thailand.

Like a tiny dark Jewel in the metropolitan. Thank you.

An excellent piece! And I love Ryder. Thank you for this.