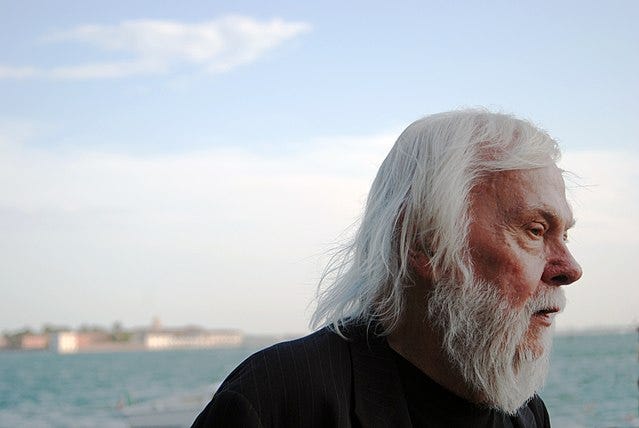

Open Canon: John Baldessari

by Thomas Larson. Initially laughed out of galleries, John Baldessari developed his "creed that the blander the subject matter, the more the artist’s capture of that blandness startles us."

Exodus • The artist John Baldessari, who died in 2020, was born in 1933, in National City, California, an industrial, working-class suburb that borders the south San Diego neighborhoods of Encanto, Skyline, and Paradise Hills. He taught at community colleges, was well-liked, and pursued the shock of the new, movements with manifestos, in the 1960s, many of which were trapped, as the critic Barry Schwabsky wrote, “between expressionist agony and academic restraint.”1 He stayed in National City and searched for venues to show his work. He got so tired of rejection that he, like lots of talented locals, left his “invisible” hometown for Los Angeles at 37. We read a lot about him these days because, post-death, art elites are finally, truly, prizing his work, one of the nimblest practitioners of Conceptualism, the postmodern irreverence that art can be about art or against art.

A trickster in the tradition of the Dadaists—put a frame around anything or stick an object in a museum and, set apart, voilà, it’s “art”—Baldessari made a series of images, combining banal snapshots, often over- or underdeveloped, with a mundane comment, in Calvin Tomkins’s phrase, “photography-based art-about-art.” He drove around National City and took Polaroids of the ordinary: local stores, billboards, street scenes. He attached witty titles like “Econ-o-Wash, 14th and Highland” to one shot or, to a whole series of photos, “The Backs of All the Trucks Passed While Driving from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, Calif., Sunday 20 Jan. 63.” These pieces noticed the unsightliness of the everyday with a kind of eventless curiosity. He dubbed one set of such photo-texts “Pure Beauty.” (His standard flippant response: “Truth is beautiful, no matter how ugly it is.”) As for his product, he conceptualized an “art” that would take minimal effort to produce—stretch a canvas, glom on via photo-emulsion a photograph, send it off to a trained sign painter to letter the title on the lower half of the canvas. The titles were tongue-in-cheek: “Is this art?” or “I will not make any more boring art.” He bent-if-not-broke our expectations about fine art as “labor-intensive”—the sedulous genius, like Rembrandt, who never leaves his atelier. Instead, Baldessari emphasized the DIY view that the very specialness of the found and the accidental, the wry and the plain, had value if only to its facetious creator.

Developing this anti-aesthetic in the late 1950s, early 1960s, Baldessari pitched local galleries and was laughed out. As object and muse, National City, famous for its “Mile of Cars,” not its licentious spirit, was an oxymoron—still is. Better put, it’s a place that isn’t quite “here” or “there,” because of its banality, its obviousness, yet is seen, recorded, and interpreted by the artist. If anywhere, the unnoticeable is in-between, its identity desultory, its location ever near-to. In the environs of San Diego, National City is near-to but not the beach; it’s near-to but not downtown; it’s near-to but not the Navy-anchored bay; it’s near-to but not the border with Mexico. It’s close by the jewels of Balboa Park, the coastal surf funk, fresh seafood restaurants, harbor cruises, the Vietnamese strip malls—all that just a short drive away, provided, these days, you can find parking. National City is set apart but so is any other mundane landmark: Baldessari’s point.

Nothing stirring, Baldessari sought action in the mecca to the north, artists and art investors in Los Angeles, the historical ground of the California Impressionists and Pop Art formalists like Ed Ruscha. Baldessari I-5’ed himself to LA and studied at the Otis Art Institute (1957-1959), after which he returned to National City and taught classes. (Famously, he had a degree not in studio art but in art education and was an inspiring teacher. Ever the self-mocking truth teller, he said, “I didn’t even know who Matisse or Picasso were when I went to college.”) In the 1960s, he would drive to LA once a month to view exhibits (nothing in San Diego stirred him), among them a Duchamp retrospective in Pasadena as well as Andy Warhol’s first one-person show of Campbell’s soup cans at the Ferus Gallery near the Sunset Strip. After Baldessari fashioned the photo-text images, David Antin, of the newly staffed Fine Arts Department at UC San Diego, arranged for a show—where else but the very hip Molly Barnes Gallery in LA. Antin said later that “There was a deadpan comedy about those literal pictures of a desperately uninteresting town [National City]—the image of provincialism as a front for considerable intelligence and wit.”

Which, because of such praise, invites the question: How much can a desperately sad and plain-Jane hometown absorb one’s artistic interest? Apparently, quite a lot.

Though very few works he did until 1968 attracted buyers, Baldessari felt the photo-text pieces captured his nice-guy/bad-boy sensibility. Memorializing his self-definition was an epiphany: For a commemorative performance piece, he decided to burn everything (123 pieces) he’d done prior to 1966, except the photo-text images. He called the conflagration the Cremation Project and, in its honor, had the following statement notarized: “[A]ll works of art done by the undersigned [J.B.] between May 1953 and March 1966 in his possession as of July 24, 1970 were cremated on July 24, 1970 in San Diego, California.” The sole commonality these “works of art” had was that they never sold.2 To bury them, respectfully, he searched for a local mortuary who might burn the paintings; most said no until one finally agreed, but only after hours. Of the ashes left, he had them baked into “cookies” and put into a single jar: Another work of art, exiled from itself, but still, for sale.

Post-blaze, Baldessari worried that he’d never get out of National City. He was married with two kids; he loved teaching and his students but despaired—not even the Cremation Project put him on the map or into the discussion. Years later, in 1996 and lionized by contemporary critics and collectors, he recalled his “fond frustration” with San Diego as a place he knew he had to leave: “There should be more than one newspaper in the town,” he said. “There should be more than one or two art critics. That’s just for openers. The same things still remain twenty-plus years after I left San Diego. Why? Everything else has grown. I don’t get it.”3

In 1970, he took a job at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, a half-hour northeast of Los Angeles, the Disney-funded school where animators and artists of all stripes study. There, he mentored many artists (the collagist David Salle was one) who diverged from Baldessari’s conceptualism but did absorb his love of the double-take, the lie that tells the truth. Within a year of relocating to Santa Monica, he had his first New York exhibition. (Alas, none of those works sold either, so he really must be a genius!) In time, artists and critics and the fickle public cottoned-to his experimentation, perhaps, got the joke, often on them. Which funny or not still posed a fundamental question: Exactly what might art be other than what it had been?

The Way Out Is The Way Back • In 2007, to that fundamental question, the market dug deep in its pockets and produced an answer. Baldessari’s “Quality Material,” a canvas from his National City period, dated 1967-68, on which he printed this text (quality material - - - close inspection - - good workmanship. all combined in an effort to give you a perfect painting) sold at Christie’s for $4.4 million. Today, it’s worth double that.

What a minute. How’s that possible? Baldessari’s drive-by photos of corner gas stations, wry observations “stating the obvious,” a picture of a man standing in front of the trunk of a palm so that the palm seems to grow out of the man’s head, titled “Wrong,” were, by the 2000s, hanging in cutting-edge galleries and echoey art museums, bought at auction and displayed in the Park Avenue apartments of the hedge-fund horde. Who suddenly found value in his pieces? Guessing how the market works is pure divination. Still, once the critical cohort noted that Baldessari owed context and inspiration to the ridiculed backwater of National City, well, that assessment kick-started an awakening, which said, there was a plan in place, unbeknownst to every interest, including the artist, all along.

So such becomes his legacy. His hometown—and much less his LA getaway—shaped his creed that the blander the subject matter, the more the artist’s capture of that blandness startles us. Eventually, the idea is institutionalized: what in the present is not art and misunderstood may be art only the future lets us get, may be worth the investment. I find this intriguing, for it elevates—and has made permanent—the artist to seek marginalization as a rite of passage. In his own way, Baldessari had to self-marginalize his anarchic vision of National City, feel a failure for doing so, burn a good deal of the work he was right that few cared for (maybe even him), and leave his surroundings for the moneyed and academic opportunities in the artsy locus 100 miles north. There, he manifested recognition, in a sense, agenting his own reception. I wonder whether this self-representation, the hyper-individualizing of the artist as brand from the get-go (think Jeff Koons, Thomas Kinkade), wasn’t Baldessari’s discovery, which nowadays is de rigueur for the “influencer.”

Perhaps this life-art mirror, indebted to Duchamp and John Cage, rewired Baldessari as well, in the 1960s and throughout his career. As art critic Hugh Davies has written, National City is “no longer an artistic wilderness and certainly [the artist has become] a prophet in his own land.”4 Indeed, his recording its uneventuality and abandoning it for fame and fortune elsewhere is a grand paradox. And yet the grandness congeals only after his death when we see that the way out of National City is also the way back. To redefine home as exile means having both and neither.

Exile • For me, Baldessari’s “meaning” resides less in his art and more in his life, the gutsy use, elegant and inelegant, of his escape hatches. (I admit to my bias on how the artist’s autobiography creates the artist’s creative content, in part, because he illustrates my thesis—where he’s from and what he left says the most about his composition. I realize such may resemble a People magazine approach to cultural interpretation, but so be it.) Another fascination about Baldessari is that because of his love of the superficial, he’s comfortable being banished from the craftsman and aesthetic sides of art, landing, instead, between huckster and dilettante, a playfulness reminiscent of the Futurists and Fluxus. Think of the perseverance that artists had to have 50 years ago to be so far outside convention as one of few means to christen a new convention.

Exile seems right—to leave or to be forced out. In his case, personal, geographical, artistic, a clumsily confounding artist-less art. Namesaked in his classic text-piece: Everything Is Purged from This Painting But Art, No Ideas Have Entered This Work. Voilà, “a painting,” which is an artistic product since “no ideas have entered the work.” Hah! The very idea is that ideas have been “purged” so the result can only be “art.” Hah! Hah!

Once Baldessari became an “LA artist,” he announced that he “wasn’t an LA artist” and, instead, fancied himself a global creator. In his career, he left any group that critics repurposed him among, even if it meant dodging categories was his celebrity more so than his painting, famous for avoiding fame. What good was trading the obscurity of the hapless non-scenery in San Diego with the buddy-boy fraternity of the LA art world when the whole point was to shed identities, not to accrue them? Baldessari wanted to be everywhere and nowhere, conceptual and post-conceptual and nonconceptual. Rootlessness propounded theorylessness, and he did yeoman’s work resisting artistic tags—minimalist, deconstructionist, anti-hierarchical, obscurantist, significant, none of which fit until, later in the game, the art circles proclaimed him an exemplary postmodernist (the all-purpose tag for the many who have never fit). Which meant, as Christopher Butler writes, “It was not the object itself” that counted in the postmodernist’s work “but the conceptual processes behind it.”5 By all means, something must count. Such concepts seem to require an idea before an artist executes. Or the artist needed to think relentlessly about the making of the work while the work was being made, so the work didn’t sideline its idea and fall to improvisation, by definition, the absence of thought: first stroke, best stroke. The work had to be the end result of an inner process that thought it into evidentiary being and, at the same time, seemed whimsically of the moment.

Much art, at least, the derring-do, has this quality of exile—to abscond and become itself because it’s been uprooted. It has left the realm of what it was or should have been, for those things were too limiting. Baldessari violated what the artist and critic had agreed to, namely, that prevalent images and techniques and membership in a historical continuity constituted the content. From that he was exiled or he self-exiled. Take your pick. And there’s a tasty third slice: Baldessari first made a lot of stuff, then jettisoned himself and the pieces (by burning most of it) to enter a new naked realm and meander without an idea where he was except elsewhere.

It’s also exilic to flee, that is, prior to being forced out, deracinated. Realizing (often too late) that the authorities are coming for your removal. The Jews exiled from their native land in Palestine and in their adopted home, Central Europe, millennia later. Adam and Eve banished from the Garden. In some religions, a people spend their lives in exile from their true home, Heaven for many, a Rest Area from which they came and to which they’ll return. (God sent them out of Paradise and onto a baleful earth so they’d appreciate the little house on the prairie once they returned, conditionally, of course.) Add Dante, exiled from Florence, or Pasternak, exiled within Russia, for the ripest of sins: poetry against church and state. To be expelled, sent off, isled like Napoleon or Papillon. To be expatriated. Or, contrarily, to be exiled for treason and wander the seas by ship like the man without a country.

And another meaning for exile: to thin, to attenuate, to reduce: to become meager, scanty, lean, barren, poor, to disembowel. The OED brings this to life: “an actual division of the whole into so many subtile, exile, invisible particles.” A whole can be minced and produce not a loss of matter but matter’s far-flung disaggregation and disbursement. Broken away from its original constitution. A scattering. The Big Bang expending matter into an expansively exiling universe.

Attending this sense of dispersal is the transference of reality to appearance, a concept whose loveliness Baldessari might have approved: “It is not . . . the paper that is, in fact, the substitute for money but something still more exile; the promise . . . stamped upon it.”

That an entity can have a representative value that is exiled from itself yet still, somehow, retain its value. A painting sells for $1 million, its worth no longer intrinsic, if it ever was. Its worth resides solely in its exchange—the canvas as a commodity for the person who possesses the money to buy and own it: provenance.

Enlarge that to the artist who must leave his home/hometown for recognition, a career, or just raw adventure. A constituent necessity within that home/hometown is missing. The artist wants it and espies it elsewhere, in the gallery promises of Los Angeles or New York or Houston, of a savvy market and its critical buzz. And there I find the final lesson of Baldessari: the place from which he is exiled or self-exiles must exist as less than, as a reverse elsewhere. Once he got to LA and felt some degree less homeless, of settledness, he realized that ending up there, not here, was his fate. The fate of the pushed out was to begin pushing himself.

Why has no one but me, a literary critic, made this point?

I don’t get it.

Journalist, book/music critic, and memoirist Thomas Larson is the author of Spirituality and the Writer: A Personal Inquiry (Swallow Press). He has also written The Sanctuary of Illness: A Memoir of Heart Disease (Hudson Whitman), The Saddest Music Ever Written: The Story of Samuel Barber’s ‘Adagio for Strings’ (Pegasus Press), and The Memoir and the Memoirist: Reading and Writing Personal Narrative (Swallow Press). He is a 24-year staff writer of longform journalism for the San Diego Reader, a seven-year book review editor for River Teeth, and a former music critic for the Santa Fe New Mexican. www.thomaslarson.com

“Burning Man.” Bookforum, Sep/Oct/Nov 2012.

Here, I must expose an irony buried in an enigma. According to Yve-Alain Bois, in the catalogue raisonné of Baldessari’s work, he did not burn “all works of art” over a thirteen-year period. He apparently “disowned” the 123 unsold works, sliding them into the gas chamber (see photos), while as many as 132 of his other works were in the possession of others, several with his sister, and were not burned. Have these been tracked down? PhD students continue to look.

In 1996, for an anniversary show of his photo-texts, Baldessari returned to the form, this time with color. One particularly loud piece is Sunny Donuts, 724 Highland Avenue, National City, Calif. The photo catches a Yellow Cab with a Pacers sign (a strip club) on top driving by, a yellow “Checks Cashed” sign on a tower overhead, a red pickup truck and two banners in Italian colors advertising “Espresso,” which is for sale in “Sunny Donuts.” The red pickup and the yellow taxi clash so strongly that we see how color Disneyfies or demonizes (or beautifies, depending on your point of view) the city in ways black-and-white photographs seldom do.

John Baldessari: National City. Hugh Davies, et alia. Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, 1997.

Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, page 81.